The juxtaposition of these two names is not intended to suggest the task of identifying and expounding upon dependencies and autonomies, similarities or differences, an originality or independence of one vis-à-vis the other. What one most needs to learn from both, if one is to understand them - the dialectical method - applies, as with all genuine thinkers, first and foremost to them themselves, and their relation. Dichotomies such as ‘dependent’ or ‘non-dependent’ are particularly inappropriate in this case. It is dialectically self-evident that oppositions given special emphasis, such as (historical) materialism vs. idealism, economics vs. ideology, or even sharp polemical negations, merely demonstrate a particularly intense type of dialectical connection.

A few years ago, in 1927, an unpublished Critique of Hegel’s Doctrine of the State appeared for the first time in the major historical-critical edition of Karl Marx’s complete works that Ryazanov is preparing. Written in 1843, it may reveal even more about the young Marx than his well-known Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher of 1844, whose comments on Hegel’s philosophy of the state are very fierce and scornful. But here we are not concerned with the details of Marx’s response to Hegel’s juridico-philosophical justifications for the constitutional monarchy of the time. What seems to me more important is the following. The matter on which Hegel, in his twilight years, staked his person, the recognition of constitutional monarchy as the state standing above civil society [bürgerliche Gesellschaft], appears to the historical consciousness of this young Hegelian as a status quo long since historically obsolete, legitimacy its only remaining basis of self-assertion. The arguments of his teacher are to him a foolishly vacuous apology, a pleading and sophistic defence of existing circumstances and orders. In these comments and interjections, from an unknown 25-year-old editor on a famous and well-established philosopher of the state, Hegel is nothing but a reactionary; or more exactly, since genuine reactionaries, in the sense of a reverse transformation, are very rare, the advocate of a complacent status quo. Marx, naturally, appears as the radical revolutionary. And yet it was precisely the Hegelian method and dialectic that Marx employed. He knew that, quite apart from all its services in the politics of the day, Hegel’s philosophy and dialectical method allowed for no stasis or rest, and, in that regard, it was, and remained, the most revolutionary piece of philosophy humanity had then produced. As a revolutionary, the only question for him was to apply this method to reality, to concrete present-day political reality. For according to this philosophy, spirit and reason are nothing but present spirit, and all true historical knowledge is knowledge of the present. The reason of what is actual and the actuality of what is rational is always current and contemporary, although not, of course, in the sense of day-to-day politics, or petty interests in private happiness. For Marx, the political actuality of the nineteenth century lay in the fact that its state was not the realm of objective and present spirit which Hegel had declared it to be. In this transitional stage, it was partly a relic of historically obsolete epochs, and partly an instrument of an essentially economic, industrial bourgeois society. Thus it was a question of rationally comprehending the actuality of this economically determined bourgeois society as a moment of the dialectical process. By the power of a specifically Hegelian logic, the Hegelian had to venture into economics and grasp the economic, because, in the dialectical process of concrete political becoming, the then state, which still appeared to hold a monopoly on the political, had actually already fallen victim to the ruse of the idea, and the active substances of the political were now situated in a seemingly apolitical, economically determined industrial society.

It is astonishing how quickly and confidently the young Marx, led by philosophy, or rather Hegelian philosophy, became aware of this process, which nowadays is easily understood. Even if the late Hegel were just an expression of the complacent status quo of that Biedermeier period, one would still have to respect him for possessing the power to impel a young thinker to a polemical opposition leading straight to the heart of the matter. But today we perceive Hegel’s subtleness and irony more clearly than his contemporaries from that Biedermeier period. We know what astonishing political writings of his youth this state philosopher had lying around unpublished, and which did not appear until the end of the century. We no longer judge Hegel in his entirety from the impressions he and his school left on students in that Berlin Biedermeier period, on people such as the young Marx, or, from a different angle, the young Kierkegaard. Today, we are familiar with the Hegel who was a friend of Hölderlin, and we know that such a youth and beginning are more important than the apparent complacency of the sunset years of a man who has achieved fame. For it was the young Hegel who first defined the concept of the bourgeois [Bourgeois] as that of the man who is essentially apolitical and in need of security. The definition is found in an early piece from 1802 on the German constitution that was not published until the end of the century. I am unable to determine, on the basis of the published literature, the extent to which the concept of the ‘bourgeois’ central to Marxist thought is directly influenced by Hegel. The French usage of this term certainly made a stronger impression on Marx, not least because the social development of France prior to 1848 was more conscious and incendiary than in Germany; and, at that time, there was no bourgeoisie in Berlin or in the Rhineland Prussian state of civil servants that could match the French or even the Western German bourgeoisie in terms of its wealth and education. But the single fact that Hegel was the first to provide a politico-polemical definition of the bourgeois, and that he did so as early as 1802, is more important than all the later disputes and objections to the old Hegel. Besides, it is enough to remember that the historico-philosophical line of development Hegel constructed is thoroughly revolutionary even in a Marxist sense, since it is a line of progress in the consciousness of freedom. In the context of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, each of these three words - progress, consciousness, freedom - is a revolutionary concept. When this progress in the consciousness of freedom is a progress of humanity, essentially occurring in humanity’s consciousness, its meaning and aim leading to humanity’s freedom, their revolutionary character in that historical context reaches its true height.

But what is decisive - from the standpoint of Hegelian philosophy - is that in all the above matters, it is not a case of abstractly conceptual, moral, pedagogical or other such kinds of progress, but of the concrete dialectic of actual current political development, the workings of a spirit which is always present, never merely past, or merely future. The concepts of truth and science in Marxist scientific socialism can only be understood from such a dialectical philosophy of history. Georg Lukács has demonstrated this very forcefully. I also agree with Edgar Salin that the concept of socialism is only correctly employed to refer to a conscious theory and practice that arises from a cognition of the social and political situation as a whole. Socialism is not simply any possible type of criticism of the ills common to all epochs. It is not compassion for the unfortunate and the poor, struggle against injustice, resistance and rebellion. Neither the Gracchi brothers, nor Michael Kohlhaas or Thomas Münzer, are socialists. What is specific and concrete about the socialism of the past centuries, and thus in historico-political terms its sole essential feature, is the premise of a type of knowledge and awareness whose origin is inseparable from what Max Weber has called occidental rationalism, and which belongs, sociologically, to the development of ‘industrial society’. ‘Scientific’ [‘Wissenschaftlich’], here, means a concrete rational consciousness of one’s historical situation as a whole, and, following from this, the claim to shape the entire situation of humanity in accordance with this consciousness. This is no natural-scientific and positive, no natural-historical cognition. The necessities or laws of truths thus known are not the necessities and regularities of physical or chemical processes. The rationalism of this scientific system has the courage to do more than identify the powers of nature, and utilise them technically to ensure a ‘receding of natural limits’. It wishes to construct humanity’s history itself, grasp the present epoch and the present moment, and thereby make humanity into the master of its own fate. A purely natural-scientific rationalism could never grasp what is politically at issue, namely, the concrete situation and the concrete moment. By contrast, Hegel’s dialectical philosophy of history, if properly employed, provides a powerful means to free the concrete here and now, the hic et nunc, from the sphere of irrational intuitions or emotionally guided impressionism, and install man as the master over the irrationality of a fate ordained by God, nature, or providence.

With astonishing confidence and sureness of vision, the young Marx repeatedly emphasised, vis-à-vis the late Hegel, that state and society cannot be counterposed to one another without asking: what men, in the concrete present, today constitute the state? How can the very men who make up the animal kingdom of an apolitical, economic-egoistic society simultaneously create a state standing high above this society, as the realm of objective spirit and ethical life? What is this state, concretely, but an officialdom dominated by determinate interests, and a bureaucracy? This type of concrete thought leads him to the discovery - a historico-philosophical discovery, if I may say so - of the industrial proletariat. To him, it is the only remaining class in industrial society that can become the active bearer of further historical development, and bring about the new condition of a classless humanity. It alone remains - if I may - un-dulled by the status quo; not interested in it, not corrupted by it, and so not under its thumb. The scientific certainty [wissenschaftliche Evidenz], the characteristic inherent guarantee of the correctness of this Marxist claim, is, in structure, thoroughly Hegelian, and can only be understood in Hegelian terms. Without the dialectic of a Hegelian construction of history, it would not be apparent why, after all previous historical experience, this new class should not allow itself to be ensnared by the immense power and wealth of the capitalist world; why, in one way or another, it should not allow itself to be historically appeased by a greater or lesser bribe; or why - for this would also be empirically possible - it should not succumb to immiseration, and perish in lethargy and stupidity, as with many peoples and classes of history; or why a new migration of peoples could not transform the face of the earth, and many other entirely plausible questions. From where does Marx’s assurance come that all this will not occur? What assures him that the bourgeoisie’s final hour, the proletariat’s world-historical moment, the transition to the classless society of the future, is genuinely at hand?

In its structure, the Marxist answer to this central question is the answer of a Hegelian rationalist. Marxism’s assuredness of its scientific character is related to the proletariat as the dialectical and concrete, politico-polemical opponent of the bourgeoisie of industrial society. In consequence, and for as long as the struggle against this bourgeoisie continues, the proletariat is defined in essentially negative terms: it is the class which does not receive a share of surplus value, has no home, no family, no social guarantees, and hence is nothing but a class, without any other community. It is a social nothingness whose mere existence refutes the society in which such a nothingness is possible. By contrast, the enemy to be defeated, i.e. historically done away with, can be perceived and analysed in its concrete historicity. This is why Marx, as a Hegelian, had to venture onto economic terrain; not to do what Ricardo and other economists have done, but to grasp the bourgeois critically in his essence, and, through this critical comprehension, destroy him. If he could accomplish that, it would be proof that the bourgeoisie is a class whose historicity is revealed, and thus finished as a class. But the opposite also holds true. As long as the historical situation of this enemy class is not yet ripe, as long as the bourgeoisie is not just of the past, but still has a future, it remains impossible to discover its final world-historical formula. The inherent guarantee of both the Hegelian and the Marxist study of history moves within this circle. A correct consciousness is the proof that a new stage of development is beginning, and vice versa. Because historical knowing and historical being cannot be separated, the historical actuality of the new course is a proof that the knowledge is correct. This type of known certainty has nothing to do with abstractly rationalistic antitheses of activity and passivity, or anything of that sort. It is an expression of the contemporaneity of objective spirit, which actualises itself in humanity’s historical development, and continues to manifest itself. Whoever is not positioned actively and vitally within this process, whoever is not involved, is incapable of knowing, and sees and hears nothing, despite being constantly thrust this way and that by events. The bearers of the world-historical struggle, by contrast, located in the right moment of this process, know this process. What the Marxist Lenin said about classes, Hegel would say about peoples: they cannot be deceived. For they stand in a concrete, immediately present and specifically political situation. From within it, they can discover the distinction essential to any world-historically great politics, the distinction of friend and enemy. This is the crux of every truly Hegelian philosophy of history, and also, it seems to me, the kernel of the Marxist knowledge of the epoch and its present moment, as well as its concepts of truth and science.

_______

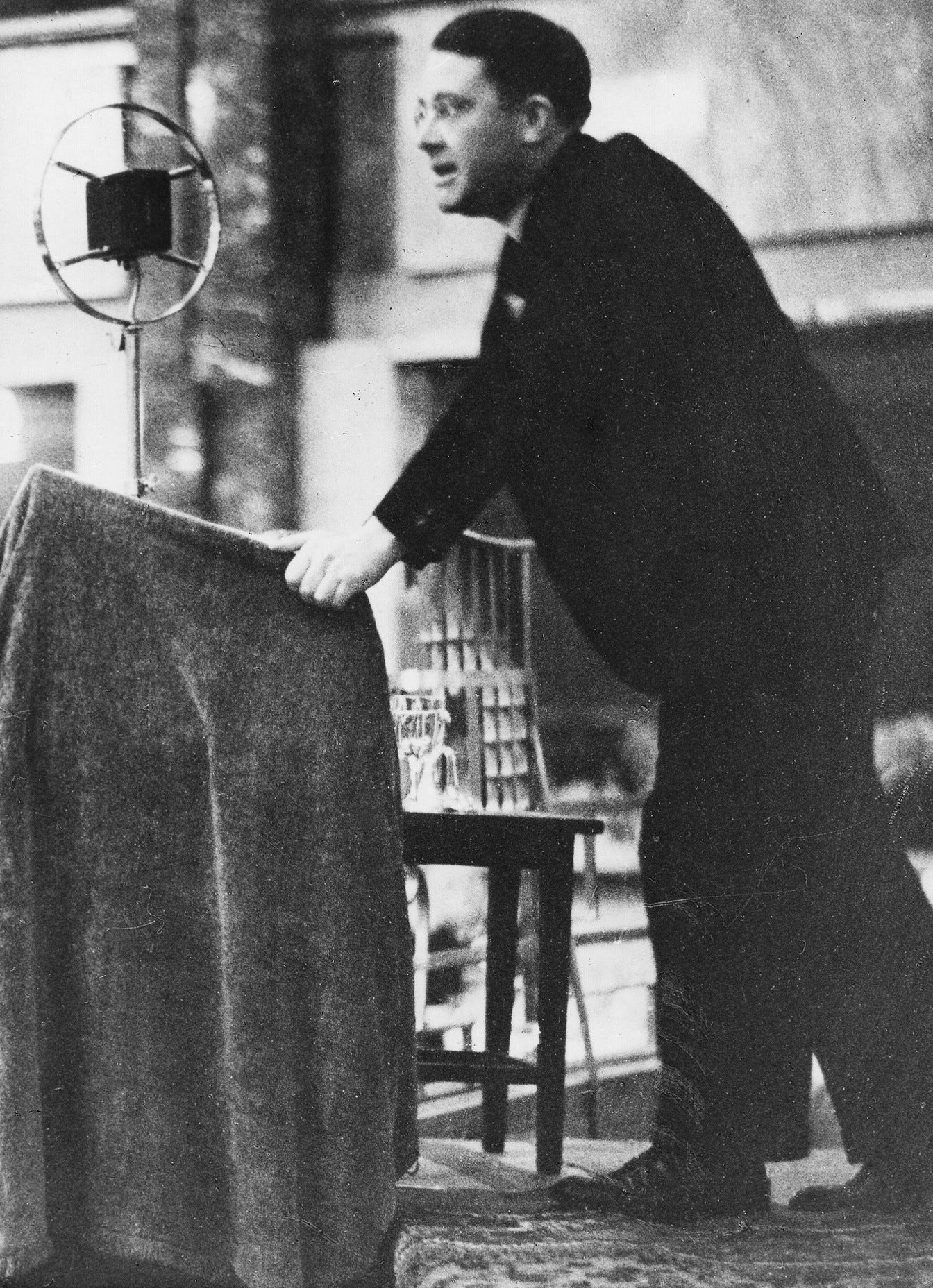

Translated by James Fumer and Max Henninger. Part of Schmitt’s radio broadcast was published as 'Hegel und Marx (1931)’ in Piet Tommissen (ed.) 1994, Schmittiana. Beiträge zu Leben und Werke Carl Schmitts. Band IV, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 48-52. It was first published in full by the Internationale Marx-Engels-Stiftung (imes) in ÜieMarx-Engels-Jahrbuch 2004, Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2005, pp. 219-27, under the title ‘Hegel und Marx. Ein Rundfunkvortrag aus dem Jahr 1931. Mit einer Nachbemerkung von Gerd Giesler’.

Great piece. In Hegelian terms then, the question is what the content of the "contemporaneity of objective spirit" is (today) - i.e. what is the historical-political situation today?. For it seems to me a valid description of our epoch what Schmitt anticipates; this new class which Marx championed did "allow itself to be ensnared by the immense power and wealth of the capitalist world" and did end in basically what he writes in this paragraph (immiseration, lethargy and stupitidy).